How to Write a Literary Analysis Paper

How to Write a Literary Analysis Paper

A literary analysis paper is more than a summary of a book, play, or poem. It is an interpretation — a carefully reasoned argument that explains how and why an author uses language, structure, and literary devices to create meaning. Through analysis, readers uncover the layers of a text and explore how its parts work together to convey the author’s purpose, message, or theme.

This guide walks you step by step through the process of writing a strong literary analysis paper, from initial reading to final revision.

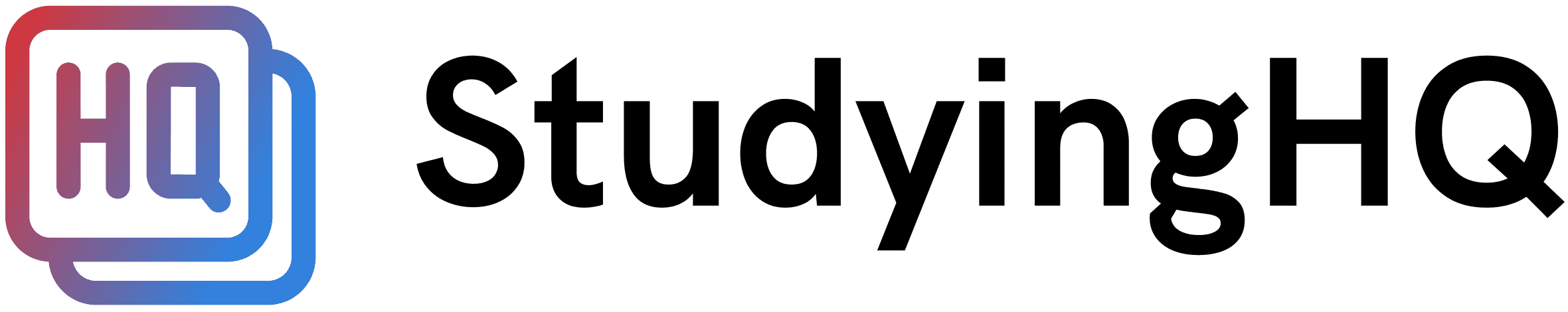

1. Read and Annotate the Text Carefully

Every successful analysis begins with a deep understanding of the text. Start by reading slowly and attentively, paying close attention to details. Highlight key passages and note recurring patterns, imagery, or ideas. As you read, ask yourself:

- What central themes or conflicts drive the story?

- How does the author’s word choice affect the tone?

- What symbols or motifs appear repeatedly?

- How do the characters’ actions and dialogue reveal their motivations?

Annotating your text is essential. Use the margins to write short notes, mark striking phrases, and record questions that arise. Look for patterns in diction, setting, or imagery that might point to larger meanings. For instance, repeated references to darkness might symbolize ignorance, fear, or moral confusion.

Remember that close reading is about noticing how the author constructs meaning, not simply what happens in the story. A literary analyst must move beyond plot summary to interpretation.

2. Develop a Strong, Arguable Thesis Statement

After you’ve read and reflected on the text, the next step is to formulate a thesis statement — your central argument or interpretation. A thesis should make an arguable claim that can be supported through textual evidence. It is not enough to state that “love is a theme in Romeo and Juliet.” Instead, your thesis should offer insight into how Shakespeare uses specific techniques to explore that theme.

For example:

“In Romeo and Juliet, Shakespeare uses light and dark imagery to symbolize the tension between love and hate, suggesting that passion, though beautiful, can also be destructive.”

A strong thesis accomplishes three things:

- It presents a clear interpretation of the text.

- It expresses a specific, arguable claim rather than a general observation.

- It guides the direction of your analysis by identifying the literary elements you will examine.

Your thesis acts as a roadmap for both you and your reader, shaping the structure and focus of your entire essay.

3. Gather and Analyze Textual Evidence

Once your thesis is in place, find evidence in the text to support it. This evidence can include direct quotations, descriptive passages, dialogue, or analysis of literary devices such as imagery, symbolism, irony, or tone.

As you collect evidence, consider the following:

- Which scenes or quotes best illustrate the claim you are making?

- How do particular words, images, or structures reinforce the author’s message?

- Are there contradictions or ambiguities that complicate your argument?

Be selective. Choose quotations that are significant and relevant rather than lengthy plot descriptions. When you include a quote, always explain its meaning and connect it to your thesis. Merely inserting quotations without analysis weakens your argument.

For accurate citations, record the page numbers or line numbers of each passage as you go. Proper documentation is a hallmark of scholarly writing.

4. Create a Detailed Outline of Your Argument

Before writing the paper, it helps to map out your ideas in a structured outline. A clear outline prevents repetition and ensures that your essay develops logically from one point to the next.

A common structure for a literary analysis essay includes:

- Introduction – Introduce the text, provide background, and state your thesis.

- Body Paragraph 1 – Discuss the first main point that supports your thesis.

- Body Paragraph 2 – Explore the next piece of evidence or theme.

- Body Paragraph 3 – Analyze another key device or example.

- Conclusion – Restate your thesis and explain its broader implications.

Each body paragraph should focus on one central idea that reinforces your overall argument. Within each paragraph, transition smoothly between ideas so that your analysis flows logically. Good organization allows readers to follow your reasoning step by step.

5. Write an Engaging Introduction

Your introduction sets the tone for the entire essay. Begin by briefly introducing the work and its author. Provide essential context, such as the title, publication date, or genre, and mention the general issue your paper will explore. Avoid lengthy plot summaries; instead, move quickly toward your analytical focus.

A strong introduction typically includes three components:

- Hook – Capture the reader’s interest with a provocative question, quote, or observation.

- Context – Offer necessary background about the text or theme.

- Thesis Statement – Clearly state your argument and outline the main points you will discuss.

Example:

“Through the character of Jay Gatsby, F. Scott Fitzgerald critiques the illusion of the American Dream. Gatsby’s pursuit of wealth and status reflects a society obsessed with material success, where moral decay lurks beneath glittering surfaces.”

This introduction presents both the focus (Gatsby and the American Dream) and the analytical stance (critique through symbolism and characterization).

6. Write Body Paragraphs Using the PEEL Method

The body of your essay is where analysis happens. Each paragraph should develop one main idea that supports your thesis. A useful strategy is the PEEL method:

- Point: Begin each paragraph with a clear topic sentence that introduces your main idea.

- Evidence: Present a specific quote, example, or reference from the text.

- Explanation: Analyze how this evidence supports your point. Discuss the author’s choices in language, tone, or structure.

- Link: Connect your analysis back to the thesis or transition smoothly to the next idea.

For example:

Point: Fitzgerald uses the green light to symbolize Gatsby’s unattainable dream.

Evidence: “Gatsby believed in the green light, the orgastic future that year by year recedes before us.”

Explanation: The recurring image of the green light captures Gatsby’s longing and the futility of his desire. Though it shines brightly across the bay, it remains forever out of reach, symbolizing the illusion of the American Dream.

Link: Thus, Fitzgerald uses the symbol to reveal the tragic nature of Gatsby’s pursuit.

Remember that analysis goes beyond restating what the text says — it explains how the author’s techniques create meaning. Avoid summarizing the plot or describing events without interpretation.

7. Write a Thoughtful and Impactful Conclusion

The conclusion is your final opportunity to leave an impression on the reader. It should do more than repeat your thesis; it should show how your analysis deepens the understanding of the text.

In your conclusion:

- Restate your thesis in new words, reflecting the insights gained through analysis.

- Summarize your main arguments succinctly.

- Discuss the broader significance of your findings — what does your analysis reveal about human nature, society, or literature?

- End with a statement that leaves the reader thinking.

For example:

“Ultimately, Fitzgerald portrays the American Dream as both seductive and hollow — a vision that drives individuals to self-destruction. Through Gatsby’s tragic idealism, the novel exposes the moral emptiness beneath the glitter of success.”

A conclusion like this ties the argument together while highlighting the enduring relevance of the text.

8. Revise, Edit, and Proofread

Writing a literary analysis is an ongoing process of refinement. Once your first draft is complete, step away from it for a short time before revising with fresh eyes. During revision, focus on both content and clarity:

- Does each paragraph clearly support your thesis?

- Are transitions smooth and logical?

- Have you avoided unnecessary summary or repetition?

- Are quotations integrated effectively and cited properly?

Next, edit for grammar, punctuation, and style. Read your essay aloud — this helps you catch awkward phrasing or missing words. Finally, ensure that your citations and bibliography follow the correct format (MLA or APA).

Revision transforms a rough draft into a polished, persuasive piece of academic writing.

Key Elements to Include in Your Analysis

In every literary analysis, your argument should draw upon several key elements of literature. Below are essential components to consider and incorporate where appropriate:

- Literary Devices:

Explore how the author uses techniques such as metaphor, symbolism, imagery, irony, and tone to develop meaning and evoke emotion. - Character Analysis:

Examine the motivations, development, and relationships of key characters. Consider how they embody themes or reflect social issues. - Themes and Messages:

Identify the central ideas and moral or philosophical questions the text raises. Ask what message the author communicates about life, society, or human behavior. - Historical and Cultural Context:

Analyze how the time period, culture, or author’s background influences the text’s themes or style. Context often reveals deeper layers of meaning. - Structure and Style:

Study the author’s narrative techniques — point of view, chronology, diction, and syntax. The way a story is told can shape its meaning as much as the story itself. - Textual Evidence:

Support every claim with direct quotations or specific references to the text. Avoid vague generalizations; always ground your interpretation in evidence.

A literary analysis paper challenges you to think critically and interpret creatively. It’s not about proving that one answer is “right” but about presenting a coherent, evidence-based argument that deepens understanding of the work.

Remember, analysis asks how and why, not just what. How does the author’s technique shape the reader’s experience? Why does the text convey certain emotions or ideas?

By reading closely, developing a clear thesis, supporting your points with solid evidence, and refining your writing, you can produce a literary analysis that demonstrates insight, precision, and academic rigor.

Literary Analysis Paper Outline

I. Introduction

- Context:

Set up the context of the novel. This includes stating the author, the title of the work, and perhaps some details as to the period the piece was written in or anything else you think would be relevant for your reader to know before reading your analysis. This is where you might also include a very short summary of the text you are analyzing (by short, Imean no more than a sentence or two).

- Thesis:

Claim:

Your claim will be your stance as to the meaning (or a meaning) behind the novel (or aspects of the novel).Example: While survival is still a major topic throughout the story, “The Open Boat” can also be read as a striving for community, . . .

- Reasons/key areas/focus:

These will be your reasons that you have that support your claim. Here is where you might delve into the use of literary devices in the text.Example:. . . . as the survivors find a sort of friendship with one another, and as they struggle together to live.

II. Reason #1

- Topic Sentence:

This sentence will state the first reason that you have supporting your claim in your thesis. Phrase this sentence in a way that restates the reason you had in your thesis, and explain how it is relevant to your claim.

Example: Multiple points throughout the story highlight the moments of the passengers finding a type of friendship with each other.

- Introduce the Evidence:

Either briefly state the context of the quote you are about to give, or give a littleglimpse into the function of the quote within the story.

Example: The narrator of the text specifically highlights the brotherhood that thesurvivors have formed:

- Quote:

Give the quote, along with the citation.

Example: “It would be difficult to describe the subtle brotherhood of men that was here established on the seas. No one said that it was so. No one mentioned it. But it dwelt in the boat, and each man felt it warm him” (Crane 370).

- Explication (un-packing the quote):

Explicating the quote involves picking out the specific words and language usedby the author within the quote. Essentially, you are saying what the quote means.

Example: This brotherhood is described as “subtle,” and the text goes on to explain that no one has verbally discussed this reality, which hints that it may not even consciously recognized by each of the men. However, even though it is not fully recognize, it is tangibly felt by each of the men, as each “felt it warm him.”

- Analysis (consider the larger significance of your explication):

After detailing what the quote means, you need to take another step outwards. What does this use of language mean? Why is this quote important? What conclusions can we draw from this evidence?

Example: As the narrator himself is commenting on the apparent brotherhood between the survivors, the conclusion is that this is no mere illusion of a single passenger . . .

- Tie-Back to Thesis:

How does this evidence support your thesis? Be sure to give a tie-back that shows how this example that you’ve analyzed proves your thesis.Example: . . . but rather a reality of the community that is drawing the four men together.

III. Section II – Reason #2

(Note: You can have as many sections as you like; two is probably a good minimum, and the maximum would depend on the paper length requirements set by your instructor. Also, if you have more than one quote/piece of evidence, you can have more than one paragraph per reason.)

A. Topic Sentence

B. Evidence

C. Quote

D. Explication

E. Analysis

F. Tie-Back to Thesis

IV. Conclusion

Restate Thesis:

Restate your thesis again in the conclusion. Be sure to change the wording so it is not repetitive, and so that it is more conducive to a conclusion, rather than an introduction.Example: Apart from the obviously seen theme of survival in the face of an in a different world, the striving of the four survivors for community in Crane’s “The Open Boat” is decidedly a major theme.

- Larger Significance of Thesis:

Take a step further outwards from your initial claim. What is the larger significance of what you’ve just argued, beyond the contents of the story?Example:While this particular story of Crane’s is usually categorized as a Naturalist piece, the search for community demonstrates a very Modernistic theme.

- Wrap-up Statement/Call for Further Inquiry:

Either provide a satisfying concluding statement to end your paper, or perhaps spark more interest in your reader by leaving them with a thought that they can pursue further.Example: Perhaps rather than lumping this piece in with Naturalism, it would be better placed as a bleed from Naturalism to Modernism.

Sample Literary Analysis Essay college

This Novel is About a Lady”: Brett Ashley in The Sun Also Rises

While Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises is told from the viewpoint of one Jake Barnes, another prominent figure within the novel is Lady Brett Ashley. In fact, in Hemingway’s original opening for the novel, he had written, “This novel is about a lady. Her name is Lady Ashley” (Qtd. in Martin 70).

Brett, as she is developed in the novel, has been painted in different lights, depending on the interpreter, ranging from a sympathetic view to one of condemnation. The portrait of her that I will attempt to show is one of a human being, caught between the ideologies of two eras.

Brett Ashley is a woman living during an age of a new femininity and sexual freedom, during the end of the repressive Victorian era. Reflecting changing behaviors, she wears pants and has her hair cropped, and she is sexually uninhibited.

Her experience may be analogous to the stereotypical college freshman who grew up in a strict household, one where the idea of drinking before twentyone is demonized, so the freshman was not educated in safe practice.

The newfound freedom is exhilarating, and the freshman is known to binge-drink, not thinking of his or her tolerance level and the consequences, such as an incapacitating hangover. The sexual promiscuity of Brett, and other women of her time period, may be viewed in the same light: after a repressive era, sex is, in a way, “new” and exciting.

However, because of the prior taboo of discussing sex, a sense of responsibility, self-respect, and self-care was likely not passed down to Brett. Because of this, she, as a “new woman,” binges on sex. This is not necessarily because she is an emasculating man-eater.

Rather, this is a reflection on her being almost child-like in her behavior, being given power without being made aware of the responsibility of it. As Martin expresses, for Brett, the need to rebel against the traditional idea of the feminine outweighs the practice of responsible sex (67-8, 71).

However, her existence during such a cultural transition takes a toll on Brett’s psychological well-being. In trying to cope with Robert Cohn’s infatuation with her, for example, she turns to alcohol: As Jake returns a bottle of Fundador to the bartender, she stops him. “‘Let’s have one more drink of that,’ Brett said. ‘My nerves are rotten’” (Hemingway 186).

As stated by Martin, “In spite of the fact that Brett tries to break free of patriarchal control, she often vacillates between the extremes of self-abnegation and self-indulgence, and her relationships… are filled with ambivalence, anxiety, and frequently alienation” (69).

Among one of her many discussions with Jake where she admits her dissatisfaction and misery, Brett confides in him that “When I think of all the hell I put chaps through. I’m paying for it all now” (34). Thus, Brett is not without a sense of guilt.

Despite this, she continues with one affair after another, knowing how it has affected the men she has been and will be with. There must then be other driving factors in her behavior beyond a desire for sexual pleasure.

Like many people of her generation, in testing out a life free of restrictive and seemingly worn-out Victorian ideologies, Brett feels disillusionment and a loss of agency after World War I, leaving her with a “moral and emotional vacuum” (Spilka 36).

She cannot even take solace in religion. When she attempts to pray for her young lover Romero before his bullfight, she becomes uncomfortable in the atmosphere of the chapel: “‘Come on,’ she whispered throatily. ‘Let’s get out of here. Makes me damned nervous’” (Hemingway 212).

She attempts to fill this void using intimate encounters with men, seeking a momentary feeling of human connection but remains unwilling to submit herself to anyone long term. This is particularly seen in her relationship with Jake, as she constantly uses him as a financial source and emotional support, all the while knowing that he is tormented by all her lovers (Spilka 42-3). Onderdonk points out that, at times, Brett appears to want a true relationship, such as with Romero, before he attempts to “tame” her (81).

Yet, as Djos notes, she generally manipulates men, asserts her dominance over them, and avoids commitment to them (143, 148). This behavior might be interpreted as a sign that the sexual freedom Brett is trying out inevitably leads to an ethical dead end.

Unlike an imperialistic government, however, Brett is a human being with a conscience, giving rise to the aforementioned guilt. This guilt, coupled with the internal void common to the Lost Generation, is what drives her and her colleagues to seek comfort in a bottle.

Often taken for a sign of immorality, alcoholism here signifies quite the opposite. It is Brett’s conscience and her discomfort with the lack of moral direction that drive her to drink. Djos presents the following theory, based on real-life alcoholics: “There is a great deal of fear here, fear of selfunderstanding, fear of emotional and physical inadequacy, and … fear of each other” (141-2).

Because Brett and her friends are travelling an unmapped road, with no signs pointing to ethical landmarks or spiritual meaning, they must deal with the uncertainty of their situation. The characters throughout the novel do seem to have shallow interactions and relationships with each other, yet the fact that so much is left unsaid between them is evidence of Hemingway’s “tip of the iceberg” style.

For them alcohol is a social lubricant, and even a means to survive day by day, minute by minute, suggesting that these characters are navigating great psychological challenges (Djos 141) and must suffer in isolation as they do so. Brett is no exception to this experience. Early on in the novel, Brett alludes to this despair when she bemoans to Jake, “Oh, darling, I’ve been so miserable” (Hemingway 32).

Brett is far from being a role model or the picture of perfection. Yet, she is not a cold-hearted succubus, either. She is a woman attempting to find her place in the wake of a war and a gender revolution, surrounded by changing ideas, gender roles, and cultural standards.

Hiding behind a wall of alcohol abuse, she struggles, as did many women of her time, between her libido and desire for freedom from patriarchy and male ownership, and her sense of guilt and discomfort with herself and others. Brett is nothing more, or less, than a human being experiencing the tumultuous waves produced by life.

Works Cited

- Djos, Matts. “Alcoholism in Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises: A Wine and

- Roses Perspective on the Lost Generation.” 1995. Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises, edited by Linda Wagner-Martin, Oxford UP, 2002, pp. 139-53.

- Hemingway, Ernest. The Sun Also Rises. Scribner, 1926.

- Martin, Wendy. “Brett Ashley as New Woman in The Sun Also Rises.” New

- Essays on The Sun Also Rises, edited by Linda Wagner-Martin, Cambridge UP, 1987, pp. 65-81.

- Onderdonk, Todd. “‘Bitched’: Feminization, Identity, and the Hemingwayesque

- in The Sun Also Rises.” Twentieth Century Literature, vol. 52, no 1, 1 Mar. 2006, pp. 61-91. Academic Search Complete. doi:10.1215/0041462X-2006-2007. Accessed 16 Sept. 2013.

- Spilka, Mark. “The Death of Love in The Sun Also Rises.” 1958. Ernest

- Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises, edited by Linda Wagner-Martin, Oxford UP, 2002, pp. 33-45.

Does the Sun Rise? A Study of Metaphors in Ernest – literary analysis example for a short story

Although Hemingway’s novel The Sun Also Rises begins with an epigraph from the biblical book of Ecclesiastes that suggests the constantly renewing cycles of the earth and of human generations, the author’s use of metaphors in this story raises the question of whether we will always be able to recover from our own destructive behavior.

If it is true that humans and the earth are resilient and that no force can disrupt the cycle of rebirth and regeneration, the novel should leave readers feeling optimistic. However, it does not end on a positive note. Instead, it ends with confirmation that even though Brett Ashley likes to imagine a happy life with protagonist Jake Barnes, they are too damaged to have one.

Jake’s cynical response to Brett’s fantasy reminds us of this point: “Isn’t it pretty to think so?” Jake’s difficulty coping with his injury, his tendency to self-medicate with alcohol, his inability to pray, and his failure to sustain an intimate relationship with another person all exemplify the irreversible destruction inflicted byWorld War I. Specifically through the metaphors of Jake’s wound and the tainted Pamplona fiesta, the novel conveys the possibility that if we are not careful, we can dangerously disrupt the cycle of renewal.

Jake’s service as an American soldier in World War I has left him with an unusual wound: he took a hit to the groin and his sexual organs were damaged. Not only does this wound affect him physically, preventing him from being able to have sex and to reproduce, but it also affects him psychologically, robbing him of masculine confidence and of the chance for an intimate relationship with the woman he loves, Brett Ashley.

Jake’s response to the injury as he looks in the mirror reveals how powerfully the scar affects him: “I looked at myself in the mirror of the big armoire beside the bed….Of all the ways to be wounded. I suppose it was funny” (38). Although Jake tries to laugh off the injury, he suffers from the constant effort to cope with it and the general effects of his war experience: “I lay awake thinking and my mind jumping around.

Then I couldn’t keep away from it, and I started to think about Brett and all the rest of it went away. I was thinking about Brett and my mind stopped jumping around and started to go in sort of smooth waves. Then all of a sudden I started to cry” (39). The wound is a constant reminder to Jake that his life is different now.

Yet it also serves as a general metaphor for the psychological wounds he and all his friends are coping with. Like Jake’s genital scar, his friends’ pain is kept well-covered. They almost never speak of the war. When Robert Cohn asks Mike Campbell if he was in the war, Mike answers, “Was I not?” And then the subject shifts to a funny story about Mike’s stealing medals earned by someone else so Mike could wear them to a formal dinner.

Although he seems fun-loving, ready to laugh and party with his companions, Mike drinks and spends money indiscriminately in order to cope with his pain. We see the characters’ dysfunctional behavior throughout the novel as the group constantly drinks and engages in distractions to cope with their own psychological wounds. The worst effects of these injuries are their inability to find hope in anything, even God, and to enjoy close and healthy

Relationships with each other.

Another metaphor employed effectively in the novel to suggest irreversible destruction is the ruined bull fights. Jake has been an aficionado of the bull fights for many years. He considers them almost sacred. He shares this feeling with his friend Montoya, at whose hotel he stays when he comes to Pamplona for the fiesta.

“I had stopped at the Montoya for several years. We never talked for very long at a time. It was simply the pleasure of discovering what we each felt.” (137). Even though Jake’s mind wanders when he goes to church now, he has been able to maintain this special experience of the bull fights. The way he describes this “art” reveals that he sees something pure in it—a chance to confront one’s fears with dignity, courage, and grace and then destroy those fears: “Romero’s bull-fighting gave real emotion, because he kept the absolute purity of line in his movements and always quietly and calmly let the horns pass him close each time” (171). Since the events recur each year during fiesta, there is a sense of renewal associated with it.

However, when Brett initiates Romero into manhood through a brief sexual affair, it not only compromises Romero’s innocence and purity as an artist, but it spoils the experience of fiesta for Jake. Montoya, his fellow aficionado blames Jake and his friends for not respecting Romero and the bull fight, and the loss of this friendship hurts Jake. Just before the group leaves town, Jake says, “We had lunch and paid the bill. Montoya did not come near us” (232).

Montoya’s previous regard for Jake will not likely be regained, since the aficion, or passion, they shared was very rare, and the affair has spoiled their bond. Like Jake and his friends’ faith in anything transcending ordinary mundane life, Jake’s experience of the bull fight has been tainted now by the dysfunctional actions of him and the rest of the group. This metaphor suggests that some kinds of destruction are permanent.

As the novel concludes, the reader wants to believe that Jake will survive and find some kind of happiness. Yet, the metaphors of Jake’s wound and the tainted bull fights suggest that some kinds of damage cannot be undone. The novel implies that, as a result of one of the most destructive wars in human history, these characters will simply have to learn to live with their injuries and cope with their lost hopes. Their hardship serves as a warning that humans should think carefully before waging war against each other.

Works Cited

Hemingway, Ernest. The Sun Also Rises. Scribner, 1926.

here’s how to cite a poem

Related Articles

Literary Analysis Essay Outline – A Step By Step Guide

How to Write a Literary Analysis Essay | A Step-by-Step Guide